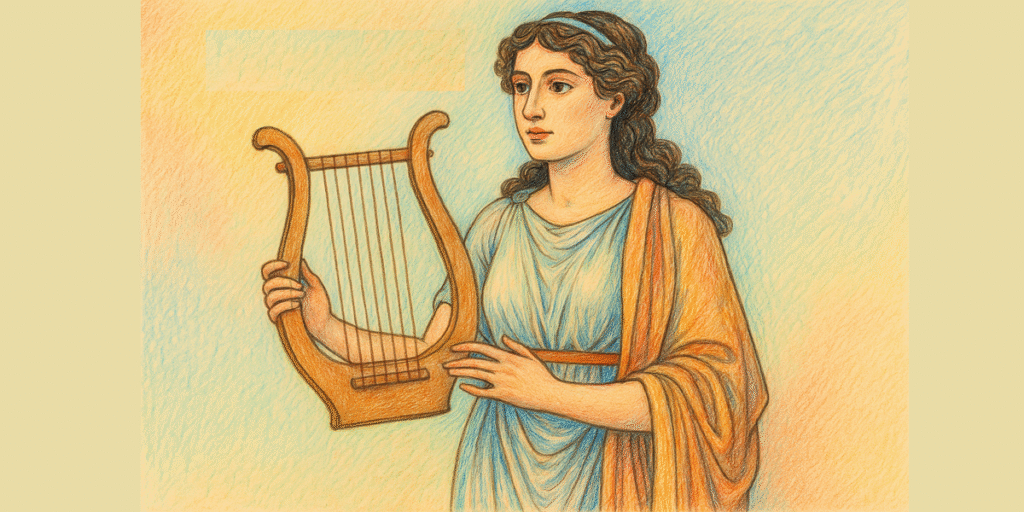

Enheduanna (c. 2285 – 2250 BCE)

Daughter of Sargon of Akkad • High Priestess of Ur • First Named Author in History

Early Life and Family Background

Enheduanna was born around 2285 BCE in the heart of the Akkadian Empire, in what is now southern Iraq. She was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad, the empire’s founder, and likely his consort. As Sargon consolidated his rule over Mesopotamia, he appointed Enheduanna to a uniquely powerful religious office—High Priestess (En-priestess) of the moon god Nanna at the city of Ur.

Role as High Priestess

At roughly age 20, Enheduanna was installed in Ur to cement her father’s political and spiritual authority over Sumerian city-states. In this capacity, she:

- Oversaw major temple complexes, managing offerings and rituals to ensure divine favor for Akkad.

- Acted as an intermediary between the worshippers of the Sumerian moon god Nanna–Sin and the secular Akkadian court.

- Traveled between cities to restore order: inscriptions suggest she revisited Girsu, Lagash, and Uruk, re-sanctifying temples that had fallen into neglect.

Literary Contributions

Enheduanna’s most enduring legacy lies in her poetry—she is the earliest author in history known by name. Fragments of her works inscribed on clay tablets include:

- “The Exaltation of Inanna” (also called “Nin-Me-Sar-Ra”) – A hymn praising the Sumerian goddess Inanna, celebrating her power over both divine and mortal realms.

- “Sargon’s Votive Hymn” – A prayer attributing Sargon’s victories to the favor of Nanna and Inanna.

- Temple Hymns – A series of songs recording rituals and mythic lore associated with various Sumerian shrines, possibly composed under her direction or attributed to her.

These compositions showcase a lyrical mastery—employing repetition, parallel structure, and evocative imagery—and reveal a syncretism of Akkadian and Sumerian religious traditions.

Political and Spiritual Influence

Beyond her literary output, Enheduanna wielded soft power across the empire. Her titles, such as “Divine Princess” and “Great Lady of the An” (sky-god) Temple, underscored her dual role as both royal envoy and sacred custodian. Inscriptions credit her with quelling rebellions and restoring temple administrations, strengthening Akkadian hegemony through religious unification.

Later Years and Legacy

Around 2250 BCE, political shifts in Akkad led to her displacement from Ur. Whether she returned to Akkad or lived out her life elsewhere is not recorded. Millennia later, her works were rediscovered by archaeologists in the 1920s at excavations of temple libraries in Nippur and Uruk.

Enheduanna’s significance today rests on two pillars:

- Historical First – As the earliest author known by name, she reshaped our understanding of ancient literary culture.

- Cultural Bridge – Her hymns testify to the complex interplay of Sumerian and Akkadian belief systems during the empire’s zenith.

Enduring Impact

Enheduanna stands as a symbol of female authority in the ancient Near East and a testament to the power of the written word. Her voice echoes across 4,500 years, reminding us that literature, devotion, and political acumen can converge in a single, remarkable life.

I. Royal Beginnings in Akkad

Born around 2285 BCE into the burgeoning city of Akkad, Enheduanna was more than a princess—she was destiny’s instrument. As the eldest daughter of Sargon the Great, the conqueror who knit Sumerian city-states into the world’s first empire, her childhood resonated with the clangor of bronze weapons, the hum of construction on Akkad’s ziggurats, and the hush of sacred rites. From her earliest days, Enheduanna absorbed both the political ambition of her father’s court and the lyrical cadences of Sumerian temple hymns recited by her wet-nurse, a former temple singer of Nanna.

II. The Moon Priestess of Ur

At roughly twenty years old, Enheduanna embarked on a journey southward—to Ur, the famed Sumerian city of the moon god Nanna (Sin). Clad in robes of lapis lazuli and saffron, she was consecrated as En-Priestess of the Great Ziggurat, becoming the living bridge between Akkad’s military might and Ur’s ancient spirituality.

- Ceremonial Duties

- Conducted nightly offerings of bread, beer, and incense at the temple’s gilded altar

- Led processions beneath moonlit skies, her wreathed crown catching torchlight

- Oversaw scribes copying sacred myths into cuneiform tablets

- Political Mandate

- Restored order in temple districts of Lagash and Girsu, long restive under Akkadian rule

- Acted as envoy, negotiating temple revenues and local tribute

- Fostered religious unity by introducing Akkadian hymns alongside Sumerian ones

III. Crafting the World’s First Authorial Voice

Enheduanna’s clay tablets survive as fragments of a literary revolution. Writing in Sumerian, she signed her hymns with her own name—the first known instance of an author claiming individual credit.

- “The Exaltation of Inanna”

A triumphal ode in which Inanna, goddess of love and war, strides through heaven and earth. Enheduanna’s verses pulse with alternating invocations—first summoning Inanna’s strength, then her compassion—creating a vivid portrait of divine duality. - Temple Hymns

A collection of thirty-five poems, each dedicated to a different shrine across Sumer. In these hymns, she weaves local legends—such as the shepherd-god Dumuzid’s descent—into a broader tapestry of Akkadian-Sumerian myth. - Royal Votive Prayer

Written on a stele in Akkad, this work thanks Nanna and Inanna for granting Sargon victory over Elamites. Here, Enheduanna blends personal devotion with state propaganda, demonstrating her skill at persuasive rhetoric.

IV. Trials, Exile, and Resilience

Political winds shifted around 2250 BCE. A usurper led a revolt in Ur, forcing Enheduanna to flee. Her own hymn, the “Lament to the Queen of Ur,” may reflect this period of displacement—mourning the temple’s ruin while affirming her faith that Inanna would one day restore her “shepherdess.”

V. Rediscovery and Modern Legacy

Buried for centuries beneath Mesopotamian sands, Enheduanna’s tablets lay silent until 1927, when excavators at Nippur uncovered fragments of her hymns. Since then:

- Scholars have hailed her as the first named author in human history.

- Feminist writers celebrate her as an early symbol of female authority.

- Composers and artists adapt her verses into contemporary choral works and graphic novels.

VI. Enheduanna’s Enduring Voice

More than 4,500 years after her hymns first rang out under Sumer’s moonlit skies, Enheduanna continues to speak to us:

“My heart opens like a lotus under the morning sun;

My words journey beyond walls of clay to the ends of time.”

In every line she crafted, we glimpse the dawn of authorship—and the enduring power of a woman who, through poetry and prayer, shaped both empire and eternity.

“The Exaltation of Inanna”

A profound hymn in which the princess-priestess invokes Inanna’s dual nature—both warrior and nurturer—triumphantly celebrating the goddess’s dominion over heaven and earth.

Thirty-Five Temple Hymns

A sweeping series of dedicatory poems, each honoring a different Sumerian sanctuary (from Ur to Eridu). In these hymns, Enheduanna traces local creation myths, recounts divine genealogies, and prescribes ritual offerings.

“Sargon’s Votive Hymn”

Inscribed on a stela at Akkad, this prayer credits the moon god Nanna and Inanna for granting her father, Sargon, victory. It weaves state propaganda into personal devotion, illustrating how sacred verse bolstered imperial ideology.

“Lament to the Queen of Ur”

Often read as both a funeral dirge and an outpouring of exile-grief, this lament mourns the desolation of Ur’s temple precincts after a rebellion and expresses her unwavering hope for restoration under Inanna’s care.

“Prayer to the Supreme Goddess”

A shorter, solemn invocation appealing to the highest divine power for protection, healing and the safeguarding of Akkad’s borders—a work that blends personal supplication with communal well-being.

1. “The Exaltation of Inanna”

- Theme and Structure

- Opens with an invocation to Inanna as “Queen of Heaven,” then shifts to recounting how the goddess endowed Enheduanna herself with authority.

- Alternates between praise (e.g., “You who exalt the just, you who humble the proud”) and personal testimony (“I have called upon your name, and you came to my side”).

- Literary Techniques

- Uses parallelism—pairs of lines that mirror each other in syntax but invert meaning, lending a musical, almost oracular quality.

- Vivid imagery: Inanna strides in “robes of lapis and gold,” her “measures” (divine decrees) unfolding like the wings of an eagle.

- Historical Context

- Likely composed soon after Enheduanna’s arrival in Ur (c. 2270 BCE) to legitimize her priestly office by linking it directly to Inanna’s favor.

- Manuscript Tradition

- Survives in seven fragmentary copies from Nippur and Ur, indicating it was recopied by temple scribes for centuries.

2. The Thirty-Five Temple Hymns

- Scope and Purpose

- A collection dedicated to the pantheon of Sumerian shrines: from the humble “House of Nanshe” at Nina to the grand “E-anna” temple in Uruk.

- Each hymn describes the temple’s founding myth, the local deity’s character, and prescribed offerings.

- Stylistic Hallmarks

- Refrains like “May your scales balance justice, may your beams hold firm” recur across multiple hymns, creating a unifying liturgical cadence.

- Geographic details (rivers, fields, ziggurats) woven into praise, rooting the divine firmly in the landscape.

- Political Resonance

- Served as both devotional literature and a political statement—by inscribing Akkadian-style praise in Sumerian temples, Enheduanna helped weave the empire’s cultural tapestry.

- Archaeological Footprint

- Over a dozen copies have been excavated at sites as far apart as Lagash and Girsu, testifying to the hymns’ wide circulation.

3. “Sargon’s Votive Hymn”

- Content and Purpose

- A formal dedication inscribed on a commemorative stele in Akkad, this hymn records Sargon’s campaign successes as gifts from Nanna and Inanna.

- Begins: “By your command, my father’s hand conquered the mountains; by your mercy, my own soul stands unshaken.”

- Blending of Genres

- Merges royal inscription (normally dry lists of conquests) with poetic devotion—transforming state propaganda into a personal act of worship.

- Legacy

- Inspired later Mesopotamian kings to compose their own votive hymns, establishing a royal-hymnist tradition that would last for a millennium.

4. “Lament to the Queen of Ur”

- Emotional Resonance

- Unusually personal for the period: Enheduanna addresses Inanna as “Mother of my heart,” mourning the desecration of Ur’s sacred precinct.

- Lines such as “My tears have filled the courtyards; the lapis gates lie silent” convey both communal sorrow and individual vulnerability.

- Function

- Likely used in a ritual of purification and petition—inviting worshippers to join in mourning so that Inanna would be moved to restore her city.

- Textual Survival

- Only two copies survive, both damaged; yet scholars have pieced together enough to recognize its groundbreaking emotional depth.

5. “Prayer to the Supreme Goddess”

- Concise Invocation

- A shorter hymn appealing to the highest deity—possibly a syncretic fusion of Inanna and Nanna—asking for protection over grain stores, city walls, and the empire’s borders.

- Emphasizes communal welfare rather than personal or dynastic praise.

- Ritual Use

- Probably recited by temple congregations at dawn, its brevity making it ideal for daily worship alongside longer hymns.

- Cultural Significance

- Demonstrates Enheduanna’s versatility: she could craft both elaborate odes and crisp, inclusive prayers.

IX. Why These Works Matter

- Literary Innovation: Enheduanna’s use of signed authorship marks the birth of individual literary identity.

- Religious Unification: By blending Akkadian and Sumerian traditions in verse, she forged a shared spiritual language across diverse cities.

- Emotional Depth: Her laments and prayers reveal a capacity for personal expression rare in ancient religious texts.

- Enduring Influence: Centuries later, Mesopotamian poets and priests looked to her hymns as a model—her cadences echo in Neo-Babylonian and Assyrian liturgies.

1. Poetic Voice and Innovation

- Signed Authorship

Enheduanna’s decision to attach her own name to hymns was revolutionary. In an era when most devotional texts were anonymous, her self-conscious signature asserts an individual literary identity—marking the birth of authorship itself. - Linguistic Mastery

Writing in Sumerian (her second language), she wove Akkadian royal rhetoric into Sumerian lyric forms. The seamless blending of two tongues, with their distinct vocabularies and cadences, demonstrates her exceptional command of both.

2. Thematic Richness

- Divine-Human Reciprocity

Across her works, the gods are not distant abstractions but active partners. In “The Exaltation of Inanna,” for example, the goddess both empowers and is empowered by Enheduanna’s praise—suggesting a dialogic relationship rather than unilateral worship. - Political Theology

Her hymns double as statecraft. “Sargon’s Votive Hymn” reframes military conquest as a divinely bestowed gift, legitimizing imperial expansion through sacred narrative. This fusion of theology and politics foreshadows later theocratic traditions.

3. Emotional Resonance

- Personal Lament

The “Lament to the Queen of Ur” stands out for its raw grief. Few ancient texts dwell so vividly on loss and exile. Lines about “tears filling the courtyards” transform public ritual into profoundly personal testimony—aesthetic boldness rare in her time. - Inclusive Prayer

In her “Prayer to the Supreme Goddess,” she shifts from personal or dynastic concerns to communal welfare—urging protection for grain, walls, and all citizens. This inclusive tone anticipates more participatory forms of worship.

4. Ritual and Performance Context

- Musicality and Refrain

Repetitive refrains (“May your scales balance justice…”) suggest these hymns were sung or chanted, not merely read. Their rhythm and parallel structures would have aided memorization and communal performance. - Temple-Library Circulation

The wide archaeological dispersal of her hymns—from Ur to Lagash—indicates they formed a core of temple curricula. Copyists continued to recirculate her verses for centuries, cementing her status as a liturgical authority.

5. Cultural Legacy

- Model for Successors

Later Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian poets explicitly emulated her mix of royal praise and divine invocation. Enheduanna’s template endured for over a millennium. - Modern Resonance

Contemporary scholars and artists invoke her as a proto-feminist icon—her assertive authorship and spiritual leadership challenging modern assumptions about gender in antiquity.

Enheduanna’s creations are at once devotional manifestos, political manifestos, and lyrical masterpieces. They reveal a mind that understood poetry’s capacity to shape history, sanctify power, and give voice to the human soul. Her hymns remain foundational texts for anyone studying the origins of literature, liturgy, and female agency in the ancient world.